2022. 10. 2. 08:26ㆍ■ 국제/백악관 사람들

'역사상 최장수 미국 대통령' 지미 카터 98세 생일 맞아 (daum.net)

'역사상 최장수 미국 대통령' 지미 카터 98세 생일 맞아

(서울=연합뉴스) 이주영 기자 = 이미 미국 역사상 최장수 대통령으로 기록된 지미 카터 전 대통령이 1일(현지시간) 아내 로잘린(95) 여사와 함께 태어나고 자란 고향인 조지아주 작은 마을 플레인

v.daum.net

'역사상 최장수 미국 대통령' 지미 카터 98세 생일 맞아

(서울=연합뉴스) 이주영 기자 = 이미 미국 역사상 최장수 대통령으로 기록된 지미 카터 전 대통령이 1일(현지시간) 아내 로잘린(95) 여사와 함께 태어나고 자란 고향인 조지아주 작은 마을 플레인스에서 98세 생일을 맞았다.

현재 카터 전 대통령에 이어 카터 센터 이사회를 이끌고 있는 손자 제이슨 카터(47)는 이날 AP 통신과 인터뷰에서 "할아버지는 자신을 위한 신의 계획에 대한 믿음을 갖고 98번째 생일을 맞고 있다"며 "자신의 현재와 미래에 평화와 행복을 느끼는 할아버지의 모습을 보는 것은 우리 모두에게 축복"이라고 말했다.

이어 "할아버지는 이날이 그가 가장 좋아하는 메이저리그(MLB) 애틀랜타 브레이브스의 경기를 TV로 지켜보는 평범한 하루가 되기를 바라고 있다"며 "이번 주말에 그가 브레이브스의 모든 경기를 볼 거라고 확신한다"고 덧붙였다.

1976년 조지아주의 초선 주지사였던 카터 전 대통령은 대선에 뛰어들어 돌풍을 일으키면서 제럴드 포드 대통령을 누르고 제39대 대통령에 당선됐다.

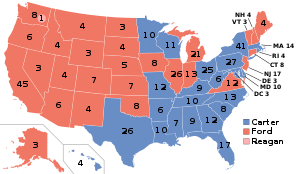

그러나 그는 4년 후 인플레이션 통제 실패와 이란 미국인 인질 사건 등으로 악화한 여론 속에서 치른 재선 도전에서 로널드 레이건 공화당 후보에게 패하고 1981년 56세의 나이에 고향 조지아주로 돌아왔다.

낙향한 카터 전 대통령 부부는 1982년 애틀랜타에 카터 센터를 설립하고서 40년째 활동을 이어가고 있다.

카터 센터는 전 세계의 평화와 인권, 공중보건 증진을 목표로 밝히고 있다. 카터 전 대통령은 이를 위해 1980년대와 1990년대 전 세계를 누볐고 2002년에는 그 공로를 인정받아 노벨평화상을 받았다.

이 때문에 카터 전 대통령은 재임 때보다 퇴임 후 더 많은 인기를 끄는 미국 대통령이라는 평가를 받는다.

페이지 알렉산더 카터 센터 소장은 "센터는 설립 이후 지금까지 세계 113개국에서 선거 감시 활동을 벌였고, 카터 전 대통령은 개인적으로도 많은 국가에서 중재자 역할을 했다"고 말했다. 그는 특히 사람에게 종양을 일으키는 기생충인 기니 벌레(guinea worm)를 퇴치한 것을 센터의 가장 큰 업적 중 하나로 꼽았다.

그는 "카터 전 대통령은 은퇴 생활을 즐기고 있다"며 "이사회에서 은퇴한 2020년 이후에도 많은 시간 자신이 시작하고 우리가 이어가고 있는 프로젝트들에 대해 생각하고 있다"고 덧붙였다.

카터 센터는 현재 개발도상국이 아닌 미국 내에서 민주적 절차에 대한 불신과 싸우는 프로그램을 진행하고 있다.

도널드 트럼프 전 대통령이 2020년 대선 결과가 조작됐다고 주장한 뒤 조지아주의 대선 투표용지 재검표를 감시해 조 바이든 당선자 승리의 정당성을 확인했고, 이번 중간선거를 앞두고는 브라이언 켐프 조지아주 주지사(공화)와 이에 도전하는 스테이시 에이브럼스 민주당 후보에게 공정한 선거 원칙에 서명할 것을 요청하기도 했다.

카터 전 대통령은 대부분 정치활동에서 손을 뗀 상태지만 최근에는 역대급 인플레이션이 엄습하자 일부 공화당 인사들이 현 정부를 공격하면서 그를 '소환'하고 있다.

제이슨 카터는 "할아버지는 매일 뉴스를 읽고 시청하며 때로는 정치권 인사들의 전화나 방문을 받기도 하지만 중간선거를 앞두고 특정 후보를 공개 지지하지는 않을 것"이라며 "그가 지금 가장 가깝게 느끼고 있는 사람들은 플레인스의 교회 교우들"이라고 말했다.

scitech@yna.co.kr

▶제보는 카톡 okjebo

저작권자(c)연합뉴스. 무단전재-재배포금지

- "부끄럽고 귀찮아" 백원짜리 잔돈 외면하는 청소년들

- '수수료 장사' 은행·증권사 5년간 접대비 1조6천억원 썼다

- 尹대통령·이재명, 국군의날 행사서 악수…대선후 첫 대면

- 웹툰 '여신강림' 완결한 작가 야옹이 "마지막화 떨면서 그려"

- 88세 국민의사 이시형 "40년간 감기 몸살 한번 없었다"

- '푸틴 충성' 체첸 수장 "러시아, 저위력 핵무기 사용해야" | 연합뉴스

- 기상청 오보로 인한 국내항공사 '결항·회항' 하루평균 1.5회

- '채널A 기자 명예훼손 혐의' 최강욱 4일 1심 선고

- 헬륨가스 마시면 왜 목소리가 변할까?

- 7살 강습생 '나 몰라라' 코스에 방치, 골절상 입게 한 스키강사 | 연합뉴스

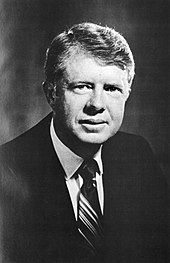

Jimmy Carter

|

Official portrait, 1978

|

|

| In office January 20, 1977 – January 20, 1981 |

|

| Walter Mondale | |

| Gerald Ford | |

| Ronald Reagan | |

| In office January 12, 1971 – January 14, 1975 |

|

| Lester Maddox | |

| Lester Maddox | |

| George Busbee | |

| In office January 14, 1963 – January 9, 1967 |

|

| District established | |

| Hugh Carter | |

|

James Earl Carter Jr.

October 1, 1924 (age 98) Plains, Georgia, U.S. |

|

| Democratic | |

| Plains, Georgia, U.S. | |

| United States Naval Academy (BS) | |

| List of honors and awards | |

| United States Navy | |

|

|

| Lieutenant | |

|

|

|

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American former politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 1971 to 1975 and as a Georgia state senator from 1963 to 1967. Since leaving office, Carter has remained engaged in political and social projects, receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002 for his humanitarian work.

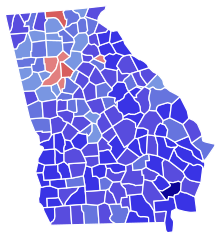

Born and raised in Plains, Georgia, Carter graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1946 with a Bachelor of Science degree and joined the United States Navy, serving on numerous submarines. After the death of his father in 1953, he left his naval career and returned home to Plains, where he assumed control of his family's peanut-growing business. He inherited comparatively little, because of his father's forgiveness of debts and the division of the estate amongst himself and his siblings. Nevertheless, his ambition to expand and grow the family's peanut farm was fulfilled. During this period, Carter was encouraged to oppose racial segregation and support the growing civil rights movement. He became an activist within the Democratic Party. From 1963 to 1967, Carter served in the Georgia State Senate, and in 1970 was elected as governor of Georgia, defeating former Governor Carl Sanders in the Democratic primary. He remained in office until 1975. Despite being a dark-horse candidate who was not well known outside of Georgia, he won the 1976 Democratic presidential nomination. In the 1976 presidential election, Carter ran as an outsider and narrowly defeated incumbent Republican president Gerald Ford.

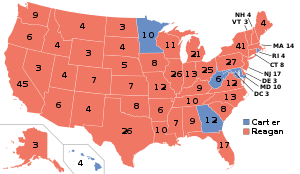

On his second day in office, Carter pardoned all Vietnam War draft evaders by issuing Proclamation 4483. During his term, two new cabinet-level departments—the Department of Energy and the Department of Education—were established. He created a national energy policy that included conservation, price control, and new technology. Carter pursued the Camp David Accords, the Panama Canal Treaties, and the second round of Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT II). On the economic front he confronted stagflation, a persistent combination of high inflation, high unemployment and slow growth. The end of his presidency was marked by the 1979–1981 Iran hostage crisis, the 1979 energy crisis, the Three Mile Island nuclear accident, the Nicaraguan Revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. In response to the invasion, Carter escalated the Cold War when he ended détente, imposed a grain embargo against the Soviets, enunciated the Carter Doctrine, and led a 1980 Summer Olympics boycott in Moscow. He is the only president to have served a full term in office and not have appointed a justice to the Supreme Court. In the 1980 Democratic Party presidential primaries, he was challenged by Senator Ted Kennedy, but won re-nomination at the 1980 Democratic National Convention. Carter lost the 1980 presidential election in an electoral landslide to Republican nominee Ronald Reagan. Polls of historians and political scientists generally rank Carter as a below-average president. His post-presidential activities have been viewed more favorably than his presidency.

In 1982, Carter established the Carter Center, aimed at promoting and expanding human rights. In 2002, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work in co-founding the Center. He has traveled extensively to conduct peace negotiations, monitor elections, and advance disease prevention and eradication in developing nations. Carter is considered a key figure in the nonprofit organization Habitat for Humanity. He has written over 30 books, ranging from political memoirs to poetry, while continuing to actively comment on ongoing American and global affairs, including the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. At 98 years old, Carter is both the oldest living and longest-lived president, as well as the one with the longest post-presidency, and his 76-year-long marriage makes him the longest-married president. He is also the third-oldest living person to have served as a state leader.

Contents

- 1Early life

- 2Naval career

- 3Farming

- 4Early political career (1963–1971)

- 5Governor of Georgia (1971–1975)

- 61976 presidential campaign

- 7Presidency (1977–1981)

- 8Post-presidency (1981–present)

- 9Political positions

- 10Personal life

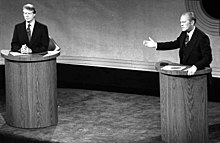

- 11Health and longevity

- 12Public image and legacy

- 13See also

- 14Notes

- 15Citations

- 16General sources

- 17Further reading

- 18External links

Early life

James Earl Carter Jr. was born on October 1, 1924, at the Wise Sanitarium (now the Lillian G. Carter Nursing Center) in Plains, Georgia, a hospital where his mother was employed as a registered nurse. Carter was the first U.S. president to be born in a hospital.[1] He was the eldest son of Bessie Lillian (née Gordy) and James Earl Carter Sr.

Carter is a descendant of English immigrant Thomas Carter, who settled in Virginia in 1635. Numerous generations of Carters lived as cotton farmers in Georgia.[2] Plains was a boomtown of 600 people at the time of Carter's birth. His father was a successful local businessman, who ran a general store and was an investor in farmland.[3] Carter's father had previously served as a reserve second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps during World War I.[3] The family moved several times during Carter's infancy.[1] The Carters settled on a dirt road in nearby Archery, which was almost entirely populated by impoverished African American families. They eventually had three more children: Gloria, Ruth, and Billy. Carter got along well with both of his parents, despite his mother often being absent during his childhood due to working long hours. Although Carter's father was staunchly pro-segregation, he allowed his son to befriend the black farmhands' children. Carter was an enterprising teenager who was given his own acre of Earl's farmland, where he grew, packaged, and sold peanuts. He also rented out a section of tenant housing that he had purchased.[1]

Education

Carter attended Plains High School from 1937 to 1941, graduating from the eleventh grade, since the school did not have a twelfth grade.[4] By that time, Archery and Plains had been impoverished by the Great Depression, but the family benefited from New Deal farming subsidies, and Carter's father took a position as a community leader. Carter was a diligent student with a fondness for reading.[citation needed] A popular anecdote holds that he was passed over for valedictorian after he and his friends skipped school to venture downtown in a hot rod. Carter's truancy was mentioned in a local newspaper, although it is not clear he would have otherwise been valedictorian.[5] As an adolescent, Carter played in the Plains High School basketball team, and also joined a youth organization named the Future Farmers of America, which helped him develop a lifelong interest in woodworking.[5]

Carter had long dreamed of attending the U.S. Naval Academy. In 1941, he started undergraduate coursework in engineering at Georgia Southwestern College in nearby Americus, Georgia. The following year, he transferred to the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, and he earned admission to the Naval Academy in 1943. He was a good student but was seen as reserved and quiet, in contrast to the academy's culture of aggressive hazing of freshmen. While at the academy, Carter fell in love with Rosalynn Smith, a friend of his sister Ruth. The two married shortly after his graduation in 1946.[6] He was a sprint football player for the Navy Midshipmen.[7] Carter graduated 60th out of 820 midshipmen in the class of 1946 with a Bachelor of Science degree and was commissioned as an ensign.[8]

Naval career

From 1946 to 1953, Carter and Rosalynn lived in Virginia, Hawaii, Connecticut, New York and California, during his deployments in the Atlantic and Pacific fleets.[9] In 1948, he began officer training for submarine duty and served aboard USS Pomfret. He was promoted to lieutenant junior grade in 1949, and his service aboard Pomfret included a simulated war patrol to the western Pacific and Chinese coast from January to March of that year. In 1951 he was assigned to the diesel/electric USS K-1, (a.k.a. USS Barracuda), qualified for command, and served in several positions, to include executive officer.[10]

In 1952, Carter began an association with the Navy's fledgling nuclear submarine program, led then by Captain Hyman G. Rickover. Rickover had high standards and demands for his men and machines, and Carter later said that, next to his parents, Rickover had the greatest influence on his life.[11] He was sent to the Naval Reactors Branch of the Atomic Energy Commission in Washington, D.C. for three month temporary duty, while Rosalynn moved with their children to Schenectady, New York.[12]

On December 12, 1952, an accident with the experimental NRX reactor at Atomic Energy of Canada's Chalk River Laboratories caused a partial meltdown, resulting in millions of liters of radioactive water flooding the reactor building's basement. This left the reactor's core ruined.[13] Carter was ordered to Chalk River to lead a U.S. maintenance crew that joined other American and Canadian service personnel to assist in the shutdown of the reactor.[14] The painstaking process required each team member to don protective gear and be lowered individually into the reactor for a few minutes at a time, limiting their exposure to radioactivity while they disassembled the crippled reactor. During and after his presidency, Carter said that his experience at Chalk River had shaped his views on atomic energy and led him to cease development of a neutron bomb.[15]

In March 1953, Carter began nuclear power school, a six-month non-credit course covering nuclear power plant operation at the Union College in Schenectady.[9] His intent was to eventually work aboard USS Seawolf, which was planned to be the second U.S. nuclear submarine. However, Carter's plans changed when his father died of pancreatic cancer two months before construction of Seawolf began,[16] and Carter obtained a release from active duty so he could take over the family peanut business. Deciding to leave Schenectady proved difficult, as Rosalynn had grown comfortable with their life there. She said later that returning to small-town life in Plains seemed "a monumental step backward." On the other hand, Carter felt restricted by the rigidity of the military and yearned to assume a path more like his father's. Carter left active duty on October 9, 1953.[17][18] He served in the inactive Navy Reserve until 1961, and left the service with the rank of lieutenant.[19] His awards included the American Campaign Medal, World War II Victory Medal, China Service Medal, and National Defense Service Medal.[20] As a submarine officer he also earned the "dolphin" badge.[21]

Farming

Earl Carter died a relatively wealthy man, having recently been elected to the Georgia House of Representatives. However, between his forgiveness of debts and the division of his wealth among heirs, his son Jimmy inherited comparatively little. For a year, Jimmy, Rosalynn, and their three sons lived in public housing in Plains.[note 1] Carter was knowledgeable in scientific and technological subjects, and he set out to expand the family's peanut-growing business. The transition from Navy to agri-businessman was difficult; his first-year harvest failed due to a drought, and Carter had to open several bank lines of credit to keep the farm afloat. Meanwhile, he also took classes and read up on agriculture while Rosalynn learned accounting to manage the business's books. Though they barely broke even the first year, the Carters grew the business and became quite successful.[22][23]

Early political career (1963–1971)

Georgia state senator (1963–1967)

Racial tension was inflamed in Plains by the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court anti-segregation ruling in Brown v. Board of Education.[24] Carter was in favor of racial tolerance and integration, but often kept those feelings to himself to avoid making enemies. By 1961 he began to speak more prominently of integration, being a prominent member of the Baptist Church and chairman of the Sumter County school board.[25][26] In 1962, a state Senate seat was opened by the dissolution of Georgia's County Unit System; Carter announced his campaign for the seat 15 days before the election. Rosalynn, who had an instinct for politics and organization, was instrumental to his campaign. Early counting of the ballots showed Carter trailing to his opponent Homer Moore, but this was the result of fraudulent voting orchestrated by Joe Hurst, the chairman of the Democratic Party in Quitman County.[27] Carter challenged the election result, which was confirmed fraudulent in an investigation. Following this, another election was held, in which Carter won against Moore as the sole Democratic candidate, with a vote margin of 3,013 to 2,182.[28]

The civil rights movement was well underway when Carter took office. He and his family had become staunch John F. Kennedy supporters. Carter remained relatively quiet on the issue at first, even as it polarized much of the county, to avoid alienating his segregationist colleagues. He did speak up on a few divisive issues, giving speeches against literacy tests and against an amendment to the Georgia Constitution which, he felt, implied a compulsion to practice religion.[29] Carter entered the state Democratic Executive Committee two years into office, where he helped rewrite the state party's rules. He became the chairman of the West Central Georgia Planning and Development Commission, which oversaw the disbursement of federal and state grants for projects such as historic site restoration.[30] In November 1964, when Bo Callaway was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, Carter immediately began planning to challenge him. The two had previously clashed over which two-year college would be expanded to a four-year college program by the state, and Carter saw Callaway—who had switched to the Republican Party—as a rival that represented aspects of politics he despised.[31] Carter was re-elected in 1964 to serve a second two-year term.[32] For some time in the State senate, he chaired its Education Committee; he also sat on the Appropriations Committee toward the end of his second term. Before his term ended, he contributed to a bill expanding statewide education funding and getting Georgia Southwestern a four-year program. He leveraged his regional planning work, giving speeches around the district to make himself more visible to potential voters. On the last day of the term, he announced his run for Congress.[33]

1966 and 1970 campaigns for governor

In Carter's first run for the governor, he ran against liberal former Governor Ellis Arnall and the conservative segregationist Lester Maddox in the Democratic primary. In a press conference, he described his ideology as "Conservative, moderate, liberal and middle-of-the-road. ... I believe I am a more complicated person than that."[34] He lost the primary, but drew enough votes as a third-place candidate to force Arnall into a runoff election with Maddox. Maddox narrowly won the runoff ballot over Arnall. In the general election, Republican Bo Callaway went on to win a plurality of the vote, but short of a 50 percent majority; the state rules empowered the Georgia House of Representatives, which had a Democratic Party majority, to elect Maddox as governor.[35] This resulted in a victorious Maddox, whose victory—due to his segregationist stance—was seen as the worse outcome to the indebted Carter.[35] Carter returned to his agriculture business, carefully planning his next campaign. This period was a spiritual turning point for Carter; he declared himself a born again Christian, and his last child Amy was born during this time.[36][37]

In the 1970 gubernatorial election, the liberal former governor Carl Sanders became Carter's main opponent in the Democratic primary. Carter ran a more modern campaign, employing printed graphics and statistical analysis. Responding to the poll data, Carter leaned more conservative than before, positioning himself as a populist and criticising Sanders for both his wealth and perceived links to the national Democratic party. He also accused Sanders of corruption, but when pressed by the media, could come up with no evidence.[38][39] Throughout his campaign, Carter sought both the black vote and "Wallace vote," referring to supporters of the prominent segregationist George Wallace of Alabama. While he met with black figures such as Martin Luther King Sr. and Andrew Young, and visited many black-owned businesses, he also praised Wallace and promised to invite him to give a speech in Georgia. Carter's appeal to racism became more blatant over time, with his senior campaign aides handing out a photograph of Sanders celebrating with black basketball players.[38][39]

Carter came ahead of Sanders in the first ballot by 49 percent to 38 percent in September, leading to a runoff election being held. The subsequent campaign was even more bitter; despite his early support for civil rights, Carter's appeal to racism grew, criticizing Sanders for supporting Martin Luther King Jr. Carter won the runoff election with 60 percent of the vote, and went on to easily win the general election against the Republican Hal Suit, a local news anchor. Once he was elected, Carter changed his tone, and began to speak against Georgia's racist politics. Leroy Johnson, a black state senator, voiced his support for Carter, saying, "I understand why he ran that kind of ultra-conservative campaign. ... I don't believe you can win this state without being a racist."[38]

Governor of Georgia (1971–1975)

Carter was sworn in as the 76th governor of Georgia on January 12, 1971. In his inaugural speech, he declared that "the time of racial discrimination is over"[40] shocking the crowd and causing many of the segregationists who had supported Carter during the race to feel betrayed. Carter was reluctant to engage with his fellow politicians, making him unpopular with the legislature.[41][42] He expanded the governor's authority by introducing a reorganization plan submitted in January 1972. Despite initially having a cool reception in the legislature, the plan was passed at midnight on last day of the session.[43] Carter ultimately merged about 300 state agencies into 22, although it is disputed that there were any overall cost savings from doing so.[44] On July 8, 1971, during an appearance in Columbus, Georgia, Carter stated his intent to establish a Georgia Human Rights Council that would work toward solving issues within the state ahead of any potential violence.[45]

In a news conference on July 13, 1971, Carter announced his ordering of department heads to reduce spending for the aid of preventing a $57 million deficit by the end of the 1972 fiscal year, specifying that each state department would be impacted and estimating that 5% more than revenue being taken in by the government would be lost if state departments continued full using allocated funds.[46] On January 13, 1972, Carter requested the state legislature to provide funding for an early childhood development program along with prison reform programs and $48 million (equivalent to $310,949,881 in 2021) in paid taxes for nearly all state employees.[47] On March 1, 1972, Carter stated a possible usage of a special session of the general assembly could take place if Justice Department opted to turn down any reapportionment plans by either the House or Senate.[48] Carter pushed several reforms through the legislature—these provided equal state aid to schools in the wealthy and poor areas of Georgia, set up community centers for mentally handicapped children, and increased educational programs for convicts. Under this program, all such appointments were based on merit, rather than political influence.[49][50] In one of his more controversial decisions, he vetoed a plan to build a dam on Georgia's Flint River, which attracted the attention of environmentalists nationwide.[51][52]

Civil rights were a high priority for Carter, the most significant of his actions being the expansion of black state employees and the addition of portraits of Martin Luther King Jr. and two other prominent black Georgians in the capitol building—an act protested by the Ku Klux Klan.[52] Carter also tried to keep his conservative allies on his side, however; Carter stated that he favored a constitutional amendment to ban busing for the purpose of expediting integration in schools on a televised joint appearance with the governor of Florida Reubin Askew on January 31, 1973,[53] and co-sponsored an anti-busing resolution with George Wallace at the 1971 National Governors Conference.[54][55] After the U.S. Supreme Court threw out Georgia's death penalty statute in Furman v. Georgia (1972), Carter signed a revised death-penalty statute that addressed the court's objections, thus re-introducing the practice in the state. Carter later regretted endorsing the death penalty, saying, "I didn't see the injustice of it as I do now."[56]

National ambition

Because he was ineligible to run for re-election, Carter looked toward a potential presidential run and engaged himself in national politics. He was named to several southern planning commissions and was a delegate to the 1972 Democratic National Convention, where the liberal U.S. Senator George McGovern was the likely presidential nominee. Carter tried to ingratiate himself with the conservative and anti-McGovern voters. However, Carter was still fairly obscure at the time, and his attempt at triangulation failed; the 1972 Democratic ticket was McGovern and Senator Thomas Eagleton.[57][note 2] On August 3, Carter met with Wallace in Birmingham, Alabama to discuss preventing the Democratic Party from losing in a landslide during the November elections.[58]

After McGovern's loss in November 1972, Carter began meeting regularly with his fledgling campaign staff. He had decided to begin putting a presidential bid for 1976 together. He tried unsuccessfully to become chairman of the National Governors Association to boost his visibility. On David Rockefeller's endorsement, he was named to the Trilateral Commission in April 1973. The following year, he was named chairman of both the Democratic National Committee's congressional and gubernatorial campaigns.[59] In May 1973, Carter warned the Democratic Party against politicizing the Watergate scandal,[60] the occurrence of which he attributed to President Richard Nixon exercising isolation from Americans and secrecy in his decision making.[61]

1976 presidential campaign

Carter announced his candidacy for president on December 12, 1974, at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. His speech contained themes of domestic inequality, optimism, and change.[62][63] Upon his entrance in the primaries, he was competing against 16 other candidates, and was considered to have little chance against the more nationally known politicians like George Wallace.[64] His name recognition was two percent, and his opponents derisively asked "Jimmy Who?".[65] In response to this, Carter began to emphasize his name and what he stood for, stating "My name is Jimmy Carter, and I'm running for president."[66] This strategy proved successful; by mid-March 1976, Carter was not only far ahead of the active contenders for the Democratic presidential nomination, but against incumbent President Gerald Ford by a few percentage points.[67] As the Watergate scandal of President Nixon was still fresh in the voters' minds, Carter's position as an outsider, distant from Washington, D.C. proved helpful. He promoted government reorganization. Carter published a memoir titled Why Not the Best? in June 1976 to help introduce himself to the American public.[68]

Carter became the front-runner early on by winning the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. His strategy involved reaching a region before another candidate could extend influence there, travelling over 50,000 miles (80,000 kilometres), visiting 37 states, and delivering over 200 speeches before any other candidate had entered the race.[69] In the South, he tacitly conceded certain areas to Wallace and swept them as a moderate when it became clear Wallace could not win it. In the North, Carter appealed largely to conservative Christian and rural voters. Whilst he did not achieve a majority in most Northern states, he won several by building the largest singular support base. Although Carter was initially dismissed as a regional candidate, he still clinched the Democratic nomination.[70]

As Lawrence Shoup noted in his 1980 book The Carter Presidency and Beyond, the national news media discovered and promoted Carter. Shoup stated that:

"What Carter had that his opponents did not was the acceptance and support of elite sectors of the mass communications media. It was their favorable coverage of Carter and his campaign that gave him an edge, propelling him rocket-like to the top of the opinion polls. This helped Carter win key primary election victories, enabling him to rise from an obscure public figure to President-elect in the short space of 9 months."[71]

During an interview in April 1976, Carter said, "I have nothing against a community that is... trying to maintain the ethnic purity of their neighborhoods."[72] His remark was intended as supportive of open-housing laws, but specifying opposition to government efforts to "inject black families into a white neighborhood just to create some sort of integration."[72] Carter's stated positions during his campaign included public financing of congressional campaigns,[73] his support for the creation of a federal consumer protection agency,[74] creating a separate cabinet-level department for education,[75] signing a peace treaty with the Soviet Union to limit nuclear weapons,[76] reducing the defense budget,[77] a tax proposal implementing "a substantial increase toward those who have the higher incomes" alongside a levy reduction on taxpayers with lower and middle incomes,[78] making multiple amendments to the Social Security Act,[79] and having a balanced budget by the end of his first term of office.[80]

On July 15, 1976, Carter chose U.S. Senator for Minnesota Walter F. Mondale as his running mate.[81] Carter and Ford faced off in three televised debates.[82] The debates were the first presidential debates since 1960.[82][83] Carter was interviewed by Robert Scheer of Playboy for the November 1976 issue, which hit the newsstands a couple of weeks before the election. While discussing his religion's view of pride, Carter said: "I've looked on a lot of women with lust. I've committed adultery in my heart many times."[84][85] This and his admission in another interview that he did not mind if people uttered the word "fuck" led to a media feeding frenzy and critics lamenting the erosion of boundary between politicians and their private intimate lives.[86] Carter began the race with a sizable lead over Ford, who narrowed the gap during the campaign, but lost to Carter in a narrow defeat on November 2, 1976.[87] Carter won the popular vote by 50.1 percent to 48.0 percent for Ford, and received 297 electoral votes to Ford's 240.[87] Carter carried fewer states than Ford—23 states to the defeated Ford's 27—yet Carter won with the largest percentage of the popular vote (50.1 percent) of any non-incumbent since Dwight Eisenhower.

Transition

Preliminary planning for Carter's presidential transition had already been underway for months before his election.[88][89] Carter had been the first presidential candidate to allot significant funds and a significant number of personnel to a pre-election transition planning effort, which subsequently would become standard practice.[90] Carter would set a mold with his presidential transition that would influence all subsequent presidential transitions, taking a methodical approach to his transition, and having a larger and more formal operation than past presidential transitions had.[90][89]

On November 22, 1976, Carter conducted his first visit to Washington, D.C. after being elected, meeting with Director of the Office of Management James Lynn and United States Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld at the Blair House, and holding an afternoon meeting with President Ford at the White House.[91] The following day, Carter conferred with congressional leaders, expressing that his meetings with cabinet members had been "very helpful" and saying Ford had requested he seek out his assistance if needing anything.[92] Relations between Ford and Carter, however, would be relatively cold during the transition.[93] During his transition, Carter announced the selection of numerous designees for positions in his administration.[94] On January 4, 1977, Carter told reporters that he would free himself from potential conflicts of interest by leaving his peanut business in the hands of trustees.[95]

Presidency (1977–1981)

Carter was inaugurated as the 39th president on January 20, 1977.[96] One of Carter's first acts was the fulfillment of a campaign promise by issuing an executive order declaring unconditional amnesty for Vietnam War-era draft evaders, Proclamation 4483.[97][98] Carter's tenure in office was marked by an economic malaise, being a time of continuing inflation and recession as well as an energy crisis in 1979. On January 7, 1980, Carter signed Law H.R. 5860 aka Public Law 96-185, known as The Chrysler Corporation Loan Guarantee Act of 1979, to bail out the Chrysler Corporation with $3.5 billion (equivalent to $11.51 billion in 2021) in aid.[99]

Carter attempted to calm various conflicts around the world, most visibly in the Middle East with the signing of the Camp David Accords;[100] giving back the Panama Canal to Panama; and signing the SALT II nuclear arms reduction treaty with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. His final year was marred by the Iran hostage crisis, which contributed to his losing the 1980 election to Ronald Reagan.[101]

Domestic policy

U.S. energy crisis

Moralism typified much of his action.[102] On April 18, 1977, Carter delivered a televised speech declaring that the current energy crisis was the "moral equivalent of war". He encouraged energy conservation and installed solar water heating panels on the White House.[103][104] He wore sweaters to offset turning down the heat in the White House.[105] On August 4, 1977, Carter signed the Department of Energy Organization Act of 1977, forming the Department of Energy, the first new cabinet position in eleven years.[106] Carter boasted that the House of Representatives had "adopted almost all" of the energy proposal he had made five months prior and called the compromise "a turning point in establishing a comprehensive energy program."[107] The following month, on October 13, Carter stated he believed in the Senate's ability to pass the energy reform bill and identified energy as "the most important domestic issue that we will face while I am in office."[108]

On January 12, 1978, during a press conference, Carter said the continued discussions about his energy reform proposal had been "long and divisive and arduous" as well as hindering to national issues that needed to be addressed with the implementation of the law.[109] In an April 11, 1978, news conference, Carter said his biggest surprise "in the nature of a disappointment" since becoming president was the difficulty Congress had in passing legislation, citing the energy reform bill in particular: "I never dreamed a year ago in April when I proposed this matter to the Congress that a year later it still would not be resolved."[110] The Carter energy legislation was approved by Congress after much deliberation and modification on October 15, 1978. The measure deregulated the sale of natural gas, dropped a longstanding pricing disparity between intra- and interstate gas, and created tax credits to encourage energy conservation and the use of non fossil fuels.[111]

On March 1, 1979, Carter submitted a standby gasoline rationing plan per the request of Congress.[112] On April 5, he delivered an address in which he stressed the urgency of energy conservation.[113] During an April 30 news conference, Carter said it was "imperative" that the House commerce committee approve the standby gasoline rationing plan and called on Congress to pass the several other standby energy conservation plans he had proposed.[114] On July 15, 1979, Carter delivered a nationally televised address in which he identified what he believed to be a "crisis of confidence" among the American people,[115] under the advisement of pollster Pat Caddell who believed Americans faced a crisis in confidence from events of the 1960s and 1970s prior to Carter's taking office.[116] The address would be cited as Carter's "malaise" speech,[115] memorable for mixed reactions[117][118] and his use of rhetoric.[119] The speech's negative reception came from a view that Carter did not state efforts on his own part to address the energy crisis and was too reliant on Americans.[120]

EPA Love Canal Superfund

In 1978, Carter declared a federal emergency in the neighborhood of Love Canal in the city of Niagara Falls, New York. More than 800 families were evacuated from the neighborhood, which had been built on top of a toxic waste landfill. The Superfund law was created in response to the situation.[121] Federal disaster money was appropriated to demolish the approximately 500 houses, the 99th Street School, and the 93rd Street School, which had been built on top of the dump; and to remediate the dump and construct a containment area for the hazardous wastes. This was the first time that such a process had been undertaken. Carter acknowledged that several more "Love Canals" existed across the country, and that discovering such hazardous dumpsites was "one of the grimmest discoveries of our modern era".[122]

Poor relations with Congress

Carter typically refused to conform to Washington's rules.[123] He avoided phone calls from members of Congress and verbally insulted them. He was unwilling to return political favors. His negativity led to frustration in passing legislation.[124] During a press conference on February 23, 1977, Carter stated that it was "inevitable" that he would come into conflict with Congress and added that he had found "a growing sense of cooperation" with Congress and met in the past with congressional members of both parties.[125] Carter developed a bitter feeling following an unsuccessful attempt at having Congress enact the scrapping of several water projects,[126] which he had requested during his first 100 days in office and received opposition from members of his party.[127] As a rift ensued between the White House and Congress afterward, Carter noted that the liberal wing of the Democratic Party was most ardently against his policies, attributing this to Ted Kennedy's wanting the presidency.[128] Carter, thinking he had support from 74 Congressmen, issued a "hit list" of 19 projects that he claimed were "pork barrel" spending that he claimed would result in a veto on his part if included in any legislation.[129] He found himself at odds with Congressional Democrats once more, with speaker of the House of Representatives Tip O'Neill finding it inappropriate for a president to pursue what had traditionally been the role of Congress. Carter was also weakened by signing a bill that contained many of the "hit list" projects he intended to cancel.[130] In an address to a fundraising dinner for the Democratic National Committee on June 23, 1977, Carter said, "I think it's good to point out tonight, too, that we have evolved a good working relationship with the Congress. For eight years we had government by partisanship. Now we have government by partnership."[131] At a July 28 news conference, assessing the first six months of his presidency, Carter spoke of his improved understanding of Congress: "I have learned to respect the Congress more in an individual basis. I've been favorably impressed at the high degree of concentrated experience and knowledge that individual members of Congress can bring on a specific subject, where they've been the chairman of a subcommittee or committee for many years and have focused their attention on this particular aspect of government life which I will never be able to do."[132]

On May 10, 1979, the House voted against giving Carter authority to produce a standby gas rationing plan.[133] The following day, Carter delivered remarks in the Oval Office describing himself as shocked and embarrassed for the American government by the vote and concluding "the majority of the House Members are unwilling to take the responsibility, the political responsibility for dealing with a potential, serious threat to our Nation." He furthered that a majority of House members were placing higher importance on "local or parochial interests" and challenged the lower chamber of Congress with composing their own rationing plan in the next 90 days.[134] Carter's remarks were met with criticism by House Republicans, who accused his comments of not befitting the formality a president should have in their public remarks. Others pointed to 106 Democrats voting against his proposal and the bipartisan criticism potentially coming back to haunt him.[135] At the start of a news conference on July 25, 1979, Carter called on believers in the future of the U.S. and his proposed energy program to speak with Congress as it bore the responsibility to impose his proposals.[136] Amid the energy proposal opposition, The New York Times commented that "as the comments flying up and down Pennsylvania Avenue illustrate, there is also a crisis of confidence between Congress and the President, sense of doubt and distrust that threatens to undermine the President's legislative program and become an important issue in next year's campaign."[137]

Economy

Carter's presidency had a troubled economic history of two roughly equal periods. The first two years were a time of continuing recovery from the severe 1973–75 recession, which had left fixed investment at its lowest level since the 1970 recession and unemployment at 9%.[138] His last two years were marked by double-digit inflation, coupled with very high interest rates,[139] oil shortages, and slow economic growth.[140] Thanks to the $30 billion economic stimulus legislation – like the Public Works Employment Act of 1977 – proposed by Carter and passed by Congress, real household median had grown by 5.2% with a projection of 6.4% for the next quarter.[141] The 1979 energy crisis ended this period of growth, however, and as both inflation and interest rates rose, economic growth, job creation, and consumer confidence declined sharply.[139] The relatively loose monetary policy adopted by Federal Reserve Board chairman G. William Miller, had already contributed to somewhat higher inflation,[142] rising from 5.8% in 1976 to 7.7% in 1978. The sudden doubling of crude oil prices by OPEC, the world's leading oil exporting cartel,[143] forced inflation to double-digit levels, averaging 11.3% in 1979 and 13.5% in 1980.[138] The sudden shortage of gasoline as the 1979 summer vacation season began exacerbated the problem, and would come to symbolize the crisis among the public in general;[139] the acute shortage, originating in the shutdown of Amerada Hess refining facilities, led to a lawsuit against the company that year by the Federal Government.[144]

Deregulation

In 1977, Carter appointed Alfred E. Kahn to lead the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). He was part of a push for deregulation of the industry, supported by leading economists, leading think tanks in Washington, a civil society coalition advocating the reform (patterned on a coalition earlier developed for the truck-and-rail-reform efforts), the head of the regulatory agency, Senate leadership, the Carter administration, and even some in the airline industry. This coalition swiftly gained legislative results in 1978.[145]

Carter signed the Airline Deregulation Act into law on October 24, 1978. The main purpose of the act was to remove government control over fares, routes and market entry (of new airlines) from commercial aviation. The Civil Aeronautics Board's powers of regulation were to be phased out, eventually allowing market forces to determine routes and fares. The Act did not remove or diminish the FAA's regulatory powers over all aspects of airline safety.[146] In 1979, Carter deregulated the American beer industry by making it legal to sell malt, hops, and yeast to American home brewers for the first time since the effective 1920 beginning of prohibition in the United States.[147] This deregulation led to an increase in home brewing over the 1980s and 1990s that by the 2000s had developed into a strong craft microbrew culture in the United States, with 6,266 micro breweries, brewpubs, and regional craft breweries in the United States by the end of 2017.[148]

Healthcare

During his presidential campaign, Carter embraced healthcare reform akin to the Ted Kennedy-sponsored bipartisan universal national health insurance.[149]

Carter's proposals on healthcare while in office included an April 1977 mandatory health care cost proposal,[150] and a June 1979 proposal that provided private health insurance coverage.[151] Carter saw the June 1979 proposal as a continuation of progress in American health coverage made by President Harry S. Truman in the latter's proposed access to quality health care being a basic right to Americans and medicare and medicaid being introduced under President Lyndon B. Johnson.[152][153] The April 1977 mandatory health care cost proposal was passed in the Senate,[154] but later defeated in the House.[155] During 1978, Carter also conducted meetings with Kennedy for a compromise healthcare law that proved unsuccessful.[156] Carter would later cite Kennedy's disagreements as having thwarted Carter's efforts to provide a comprehensive health-care system for the country.[157]

Education

Early into his term, Carter collaborated with the congress to assist in fulfilling a campaign promise to create a cabinet level education department. In an address from the White House on February 28, 1978, Carter argued "Education is far too important a matter to be scattered piecemeal among various government departments and agencies, which are often busy with sometimes dominant concerns."[158] On February 8, 1979, the Carter administration released an outline of its plan to establish an education department and asserted enough support for the enactment to occur by June.[159] On October 17, the same year, Carter signed the Department of Education Organization Act into law,[160] establishing the United States Department of Education.[161]

Carter expanded the Head Start program with the addition of 43,000 children and families,[162] while the percentage of nondefense dollars spent on education was doubled.[163] Carter was complimentary of the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson and the 89th United States Congress for having initiated Head Start.[164] In a speech on November 1, 1980, Carter stated his administration had extended Head Start to migrant children and was "working hard right now with Senator Bentsen and with Kika de la Garza to make as much as $45 million available in federal money in the border districts to help with the increase in school construction for the number of Mexican school children who reside here legally".[165]

Foreign policy

Israel and Egypt

From the onset of his presidency, Carter attempted to mediate the Arab–Israeli conflict.[166] After a failed attempt to seek a comprehensive settlement between the two nations in 1977 (through reconvening the 1973 Geneva conference,[167] Carter invited the Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and Israeli prime minister Menachim Begin to the presidential lodge Camp David in September 1978, in hopes of creating a definitive peace. Whilst the two sides could not agree on Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank, the negotiations resulted in Egypt formally recognizing Israel, and the creation of an elected government in the West Bank and Gaza. This resulted in the Camp David Accords, which ended the war between Israel and Egypt.[168]

The accords were a source of great domestic opposition in both Egypt and Israel. Historian Jørgen Jensehaugen argues that by the time Carter left office in January 1981, he was "in an odd position—he had attempted to break with traditional US policy but ended up fulfilling the goals of that tradition, which had been to break up the Arab alliance, side-line the Palestinians, build an alliance with Egypt, weaken the Soviet Union and secure Israel."[169]

Africa

In an address to the African officials at the United Nations on October 4, 1977, Carter stated the U.S.'s interest to "see a strong, vigorous, free, and prosperous Africa with as much of the control of government as possible in the hands of the residents of your countries" and pointed to their unified efforts on "the problem of how to resolve the Rhodesian, Zimbabwe question."[170] At a news conference later that month, Carter outlined that the U.S. wanted to "work harmoniously with South Africa in dealing with the threats to peace in Namibia and in Zimbabwe in particular", as well as do away with racial issues such as apartheid, and for equal opportunities in other facets of society in the region.[171]

Carter visited Nigeria from March 31 – April 3, 1978, the trip being an attempt by the Carter administration to improve relations with the country.[172] He was the first U.S. president to visit Nigeria.[173] Carter reiterated interests in convening a peace conference on the subject of Rhodesia that would involve all parties and reported that the U.S. was moving as it could.[174]

The elections of Margaret Thatcher as prime minister of the United Kingdom[175] and Abel Muzorewa for prime minister of Zimbabwe Rhodesia,[176] South Africa turning down a plan for South West Africa's independence and domestic opposition in Congress were seen as a heavy blow to the Carter administration's policy toward South Africa.[177] On May 16, 1979, the Senate voted in favor of President Carter lifting economic sanctions against Rhodesia, the vote being seen by both Rhodesia and South Africa as a potentially fatal blow to both the joint diplomacy that the United States and Britain had pursued in the region for three years and the effort to reach a compromise between the Salisbury leaders and the guerrillas.[178] On December 3, Secretary of State Vance promised Senator Jesse Helms that when the British governor arrived in Salisbury to implement an agreed Lancaster House settlement and the electoral process began, the President would take prompt action to lift sanctions against Zimbabwe Rhodesia.[179]

East Asia

Carter sought closer relations with the People's Republic of China (PRC), continuing the Nixon administration's drastic policy of rapprochement. The two countries increasingly collaborated against the Soviet Union, and the Carter administration tacitly consented to the Chinese invasion of Vietnam. In 1979, Carter extended formal diplomatic recognition to the PRC for the first time. This decision led to a boom in trade between the United States and the PRC, which was pursuing economic reforms under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping.[180] After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Carter allowed the sale of military supplies to China and began negotiations to share military intelligence.[181] In January 1980, Carter unilaterally revoked the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty with the Republic of China (ROC), which had lost control of mainland China to the PRC in 1949, but retained control the island of Taiwan. Carter's abrogation of the treaty was challenged in court by conservative Republicans, but the Supreme Court ruled that the issue was a non-justiciable political question in Goldwater v. Carter. The U.S. continued to maintain diplomatic contacts with the ROC through the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act.[182]

During Carter's presidency, the U.S. continued to support Indonesia as a cold war ally, in spite of human rights violations in East Timor. The violations followed Indonesia's December 1975 invasion and occupation of East Timor.[183] It did so even though antithetical to Carter's stated policy "of not selling weapons if it would exacerbate a potential conflict in a region of the world."[184][185]

During a news conference on March 9, 1977, Carter reaffirmed his interest in having a gradual withdrawal of American troops from South Korea and stated that he wanted South Korea to eventually have "adequate ground forces owned by and controlled by the South Korean government to protect themselves against any intrusion from North Korea."[186] On May 19, The Washington Post quoted Chief of Staff of U.S. forces in South Korea John K. Singlaub as criticizing Carter's withdrawal of troops from the Korean peninsula. Later that day, Press Secretary Rex Granum announced Singlaub had been summoned to the White House by Carter, whom he also confirmed had seen the article in The Washington Post.[187] Carter relieved Singlaub of his duties two days later on May 21 following a meeting between the two.[188][189] During a news conference on May 26, Carter said he believed that South Korea would be able to defend themselves despite reduced American troops in case of conflict.[190] From June 30 to July 1, 1979, Carter held meetings with president of South Korea Park Chung-hee at the Blue House for a discussion on relations between the U.S. and Korea as well as Carter's interest in preserving his policy of worldwide tension reduction.[191] On April 21, 1978, Carter announced a reduction in American troops in South Korea scheduled to be released by the end of the year by two-thirds, citing a lack of action by Congress in regards to a compensatory aid package for the Seoul Government.[192]

Iran

On November 15, 1977, Carter pledged that his administration would continue positive relations between the U.S. and Iran, calling its contemporary status "strong, stable and progressive".[193] When the shah was overthrown, increasingly anti-American rhetoric came from Iran, which intensified when Carter allowed the shah to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York on October 22, 1979.[194]

On November 4, a group of Iranian students took over the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. The students belonged to the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line and were in support of the Iranian Revolution.[195] Fifty-two American diplomats and citizens were held hostage for the next 444 days until they were finally freed immediately after Ronald Reagan succeeded Carter as president on January 20, 1981. During the crisis, Carter remained in isolation in the White House for more than 100 days, until he left to participate in the lighting of the National Menorah on the Ellipse.[196] A month into the affair, Carter stated his commitment to resolving the dispute without "any military action that would cause bloodshed or arouse the unstable captors of our hostages to attack them or to punish them".[197] On April 7, 1980, Carter issued Executive Order 12205, imposing economic sanctions against Iran[198] and announced further measures being taken by members of his cabinet and the American government that he deemed necessary to ensure a safe release.[199][200] On April 24, 1980, Carter ordered Operation Eagle Claw to try to free the hostages. The mission failed, leaving eight American servicemen dead and causing the destruction of two aircraft.[201][202] The ill-fated rescue attempt led to the self-imposed resignation of U.S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, who had been opposed to the mission from the beginning.

Released in 2017, a declassified memo produced by the CIA in 1980 concluded "Iranian hardliners – especially Ayatollah Khomeini" were "determined to exploit the hostage issue to bring about President Carter’s defeat in the November elections." Additionally, Tehran in 1980 wanted "the world to believe that Imam Khomeini caused President Carter's downfall and disgrace."[203]

Soviet Union

On February 8, 1977, Carter stated he had urged the Soviet Union to align with the U.S. in forming "a comprehensive test ban to stop all nuclear testing for at least an extended period of time", and that he was in favor of the Soviet Union ceasing deployment of the RSD-10 Pioneer.[204] During a press conference on June 13, Carter reported that at the beginning of the week, the U.S. would "work closely with the Soviet Union on a comprehensive test ban treaty to prohibit all testing of nuclear devices underground or in the atmosphere", and Paul Warnke would negotiate demilitarization of the Indian Ocean with the Soviet Union beginning the following week.[205] At a news conference on December 30, Carter said that throughout the period of "the last few months, the United States and the Soviet Union have made great progress in dealing with a long list of important issues, the most important of which is to control the deployment of strategic nuclear weapons" and that the two countries sought to conclude SALT II talks by the spring of the following year.[206] The talk of a comprehensive test ban treaty materialized with the signing of the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty II by Carter and Leonid Brezhnev on June 18, 1979.[207][208]

In 1979, the Soviets intervened in the Second Yemenite War. The Soviet backing of South Yemen constituted a "smaller shock", in tandem with tensions that were rising due to the Iranian Revolution. This played a role in shifting Carter's viewpoint on the Soviet Union to a more assertive one, a shift that finalized with the impending Soviet-Afghan War.[209]

In his 1980 State of the Union Address, Carter emphasized the significance of relations between the two regions: "Now, as during the last 3½ decades, the relationship between our country, the United States of America, and the Soviet Union is the most critical factor in determining whether the world will live at peace or be engulfed in global conflict."[210]

Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

Communists under the leadership of Nur Muhammad Taraki seized power in Afghanistan on April 27, 1978.[211] The new regime signed a treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union in December of that year.[211][212] However, due to the regime's efforts to improve secular education and redistribute land being accompanied by mass executions and political oppression, Taraki was deposed by rival Hafizullah Amin in September.[211][212][213] Amin was considered a "brutal psychopath" by foreign observers and had lost control of much of the country, prompting the Soviet Union to invade Afghanistan on December 24, 1979, execute Amin, and install Babrak Karmal as president.[211][212]

In the West, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was considered a threat to global security and the oil supplies of the Persian Gulf, as well as the existence of Pakistan.[212][214] These concerns led to Carter expanding collaboration between the CIA and Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), which began several months earlier when the CIA started providing some $695,000 worth of non-lethal assistance (e.g., "cash, medical equipment, and radio transmitters") to the Afghan mujahideen in July 1979.[215] The modest scope of this early collaboration was likely influenced by the understanding, later recounted by CIA official Robert Gates, "that a substantial U.S. covert aid program" might have "raise[d] the stakes" thereby causing "the Soviets to intervene more directly and vigorously than otherwise intended."[214][216] According to a 2020 review of declassified U.S. documents by Conor Tobin in the journal Diplomatic History: "The primary significance of this small-scale aid was in creating constructive links with dissidents through Pakistan's ISI that could be utilized in the case of an overt Soviet intervention ... The small-scale covert program that developed in response to the increasing Soviet influence was part of a contingency plan if the Soviets did intervene militarily, as Washington would be in a better position to make it difficult for them to consolidate their position, but not designed to induce an intervention."[215] Finally, on December 28, Carter signed a presidential finding explicitly allowing the CIA to transfer "lethal military equipment either directly or through third countries to the Afghan opponents of the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan," and to arrange "selective training, conducted outside of Afghanistan, in the use of such equipment either directly or via third country intermediation."[215] Carter's finding defined the CIA's mission as "harassment" of Soviet troops; at the time, "this was not a war the CIA expected to win outright on the battlefield," in the words of Steve Coll.[217]

Carter was determined to respond harshly to what he considered a dangerous provocation. In a televised speech on January 23, 1980, he announced sanctions on the Soviet Union, promising renewed aid and registration to Pakistan and the Selective Service System, as well as committing the U.S. to the Persian Gulf's defense.[214][216][218][219] Carter imposed an embargo on grain shipments to the USSR, tabled the consideration of SALT II, requested a 5% annual increase in defense spending,[220][221] and called for a boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow.[222] Carter's tough stance was backed enthusiastically by the British prime minister Margaret Thatcher.[214] National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski played a major role in organizing Jimmy Carter's policies on the Soviet Union as a grand strategy.[223]

The thrust of U.S. policy for the duration of the war was determined by Carter in early 1980: Carter initiated a program to arm the mujahideen through Pakistan's ISI and secured a pledge from Saudi Arabia to match U.S. funding for this purpose. The Soviets were unable to quell the insurgency and withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989, precipitating the dissolution of the Soviet Union itself.[214] However, the decision to route U.S. aid through Pakistan led to massive fraud, as weapons sent to Karachi were frequently sold on the local market rather than delivered to the Afghan rebels. Despite this, Carter has expressed no regrets over his decision to support what he still considers the "freedom fighters" in Afghanistan.[214]

International trips

Carter made twelve international trips to twenty-five countries during his presidency.[224] Carter was the first president to make a state visit to Sub-Saharan Africa when he went to Nigeria in 1978.[173] His travel also included trips to Europe, Asia, and Latin America. He made several trips to the Middle East to broker peace negotiations. His visit to Iran from December 31, 1977, to January 1, 1978, took place less than a year before the overthrow of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.[225]

Allegations and investigations

The September 21, 1977, resignation of Bert Lance, who served as director of the office of management and budget in the Carter administration, came amid allegations of improper banking activities prior to his tenure and was an embarrassment to Carter.[226]

Carter became the first sitting president to testify under oath as part of an investigation towards him,[227][228] as a result of United States Attorney General Griffin Bell appointing Paul J. Curran as a special counsel to investigate loans made to the peanut business owned by Carter by a bank controlled by Bert Lance and Curran's position as special counsel not allowing him to file charges on his own.[229][note 3] Curran announced in October 1979 that no evidence had been found to support allegations that funds loaned from the National Bank of Georgia had been diverted to Carter's 1976 presidential campaign, ending the investigation.[230]

1980 presidential campaign

Carter's campaign for re-election in 1980 was based primarily on attacking Ronald Reagan. The Carter campaign frequently pointed out and mocked Reagan's proclivity to gaffes, using his age and perceived lack of connection to his native California voter base against him.[231] Later on, the campaign used similar rhetoric to the Lyndon B. Johnson 1964 presidential campaign, intending to portray Reagan as a warmonger that could not be trusted with the nuclear arsenal.[232] Carter attempted to deny the Reagan campaign $29.4 million (equivalent to $96,689,903 in 2021) in campaign funds, due to dependent conservative groups already raising $60 million to get him elected – a number which exceeded the limit of campaign funds. The request was later denied by the Federal Election Commission.[233]

Carter later wrote that the most intense and mounting opposition to his policies came from the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, which he attributed to Ted Kennedy's ambition to replace him as president.[234] After Kennedy announced his candidacy in November 1979,[235] questions regarding his activities during his presidential bid were a frequent subject of Carter's press conferences held during the Democratic presidential primaries.[236][237] Kennedy, despite winning key states such as California and New York, surprised his supporters by running a weak campaign, leading to Carter winning most of the primaries and securing renomination. However, Kennedy had mobilized the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, which gave Carter weak support in the fall election.[238] Carter and Mondale were formally nominated at the 1980 Democratic National Convention held in New York City.[239] Carter delivered a speech notable for its tribute to the late Hubert Humphrey, whom he initially called "Hubert Horatio Hornblower",[240] and Kennedy made the infamous "The Dream Shall Never Die" speech, in which he criticized Reagan and gave Carter an unenthusiastic endorsement.

Aside from Reagan and Kennedy, he was opposed by centrist John B. Anderson, who had previously contested the Republican presidential primaries, and upon being defeated by Reagan, re-entered as an independent. Anderson advertised himself as a more liberal alternative to Reagan's conservatism.[241] As the campaign went on, however, Anderson's polling numbers dropped as his supporter base was gradually pulled towards either Carter or Reagan.[242] Carter had to run against his own "stagflation"-ridden economy, while the hostage crisis in Iran dominated the news every week. He was attacked by conservatives for failing to "prevent Soviet gains" in less-developed countries, as pro-Soviet governments had taken power in countries including Angola, Ethiopia, Nicaragua and Afghanistan.[243] His brother, Billy Carter, caused controversy due to his association with Muammar Gaddafi's regime in Libya.[244] He alienated liberal college students, who were expected to be his base, by re-instating registration for the military draft. His campaign manager and former appointments secretary, Timothy Kraft, stepped down some five weeks before the general election amid what turned out to have been an uncorroborated allegation of cocaine use.[245]

On October 28, Carter and Reagan participated in the sole presidential debate of the election cycle in which they were both present – due to Carter refusing to partake in debates with Anderson.[246] Though initially trailing Carter by several points,[247] Reagan experienced a surge in polling following the debate.[248] This was in part influenced by Reagan deploying the phrase "There you go again", which became the defining phrase of the election.[249] It was later discovered that in the final days of the campaign, Reagan's team acquired classified documents used by Carter in preparation for the debate.[250] Reagan defeated Carter in a landslide, winning 489 electoral votes. The Senate went Republican for the first time since 1952.[251] In his concession speech, Carter admitted that he was hurt by the outcome of the election but pledged "a very fine transition period" with President-elect Reagan.[252]

Post-presidency (1981–present)

Shortly after losing his re-election bid, Carter told the White House press corps of his intent to emulate the retirement of Harry S. Truman and not use his subsequent public life to enrich himself.[253]

Diplomacy

Diplomacy has been a large part of Carter's post-presidency. These diplomatic efforts began in the Middle East, with a September 1981 meeting with prime minister of Israel Menachem Begin,[254] and a March 1983 tour of Egypt that included meeting with members of the Palestine Liberation Organization,[255]

In 1994, president Bill Clinton sought Carter's assistance in a North Korea peace mission, during which Carter negotiated an understanding with Kim Il-sung.[256][257] Carter went on to outline a treaty with Kim, which he announced to CNN without the consent of the Clinton administration to spur American action.[258]

In 2006, Carter stated his disagreements with the domestic and foreign policies of Israel while saying he was in favor of the country,[259][260] extending his criticisms to Israel's policies in Lebanon, the West Bank, and Gaza.[261]

In July 2007, Carter joined Nelson Mandela in Johannesburg, South Africa, to announce his participation in The Elders, a group of independent global leaders who work together on peace and human rights issues.[262][263] Following the announcement, Carter participated in visits to Darfur,[264] Sudan,[265][266] Cyprus, the Korean Peninsula, and the Middle East, among others.[267] Carter attempted traveling to Zimbabwe in November 2008, but was stopped by President Robert Mugabe's government.[268] In December 2008, Carter met with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad,[269][270] and in a June 2012 call with Jeffery Brown, Carter stressed Egyptian military generals could be granted full power executively and legislatively in addition to being able to form a new constitution in favor of themselves in case their announced intentions went through.[271]

On August 10, 2010, Carter traveled to North Korea to secure the release of Aijalon Gomes, successfully negotiating his release.[272][273] Throughout the latter part of 2017, as tensions between the U.S. and North Korea persisted, Carter recommended a peace treaty between the two nations,[274] and confirmed he had offered himself to the Trump administration as a willing candidate to serve as diplomatic envoy to North Korea.[275]

Views on successive presidents

Carter began his first year out of office with a pledge not to critique the new Reagan administration, stating that it was "too early".[276] Despite siding with Reagan on issues like building neutron arms after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan,[277] Carter frequently spoke out against the Reagan administration. He denounced many of Reagan's actions in the Middle East;[278] in 1987, Carter insisted that he was incapable of preserving peace in the Middle East.[279] Carter condemned the handling of the Sabra and Shatila massacre,[280] the lack of efforts to rescue and retrieve four American businessmen from West Beirut in 1984,[281] Reagan's support of the Strategic Defense Initiative in 1985,[282] and his claim of an international conspiracy on terrorism.[283] In 1987 he also criticized Reagan for conceding to terrorist demands,[284] the nomination of Robert Bork for the Supreme Court,[285] and his handling of the Persian Gulf crisis.[286]

On January 16, 1989, prior to the inauguration of George H. W. Bush, Carter expressed to fellow former president Ford that Reagan had experienced a media honeymoon, saying that he believed Reagan's immediate successor would be less fortunate.[287]

Carter had a mostly negative relationship with Bill Clinton; despite Clinton being the first Democrat elected in 12 years, Carter and his wife were snubbed from the inauguration ceremony. Carter criticised Clinton for the morality of his administration, particularly for the Monica Lewinsky scandal and the pardon of Marc Rich.[288]

During the presidency of George W. Bush, Carter stated his opposition to the Iraq War,[289] and what he considered an attempt on the part of Bush and Tony Blair to oust Saddam Hussein through the usage of "lies and misinterpretations".[290] In May 2007, Carter stated the Bush administration "has been the worst in history" in terms of its impact in foreign affairs,[291] and later stated he was just comparing Bush's tenure to that of Richard Nixon.[292] Carter's comments received a response from the Bush administration in the form of Tony Fratto saying Carter was increasing his irrelevance with his commentary.[293] By the end of Bush's second term, Carter considered Bush's tenure disappointing, which he disclosed in comments to Forward Magazine of Syria.[294]

Though he praised President Obama in the early part of his tenure,[295] Carter stated his disagreements with the use of drone strikes against suspected terrorists, Obama's choice to keep Guantanamo Bay detention camp open,[296] and the current federal surveillance programs as disclosed by Edward Snowden."[297][298]

During the Trump presidency, Carter spoke favorably of the chance for immigration reform through Congress,[299] and criticized Trump for his handling of the U.S. national anthem protests.[300] In October 2017, however, Carter defended President Trump in an interview with The New York Times, criticizing the media's coverage of him, stating that the media has been harsher on Trump "than any other president certainly that I've known about."[301][302] In 2019, Carter received a phone call from Trump in which he expressed concern that China was "getting ahead" of the United States. Carter agreed, stating that China's strength came from their lack of involvement in armed conflict, calling the U.S. "the most warlike nation in the history of the world."[303]

Presidential politics

Carter was considered a potential candidate in the 1984 presidential election,[304][305] but did not run and instead endorsed Walter Mondale for the Democratic nomination.[306][307] After Mondale secured the nomination, Carter critiqued the Reagan campaign,[308] spoke at the 1984 Democratic National Convention, and advised Mondale.[309] Following the election, in which President Reagan defeated Mondale, Carter stated the loss was predictable because of the latter's platform that included raising taxes.[310]

In the 1988 presidential election, Carter ruled himself out as a candidate once more and predicted Vice President George H. W. Bush as the Republican nominee in the general election.[311] Carter foresaw unity at the 1988 Democratic National Convention,[312] where he delivered an address.[313] Following the election, a failed attempt by the Democrats in regaining the White House, Carter said Bush would have a more difficult presidency than Reagan because he was not as popular.[314]

During the 1992 presidential election, Carter met with Massachusetts Senator Paul Tsongas who sought out his advice.[315] Carter spoke favorably of former Governor of Arkansas Bill Clinton,[316] and criticized Ross Perot, a Texas billionaire who was running as an independent.[317] As the primary concluded, Carter spoke of the need for the 1992 Democratic National Convention to address certain issues not focused on in the past,[318] and campaigned for Clinton after he became the Democratic nominee in the general election,[319] publicly stating his expectation to be consulted during the latter's presidency.[320]

Carter endorsed Vice President Al Gore days before the 2000 presidential election,[321] and in the years following voiced his opinion that the election was won by Gore,[322] despite the Supreme Court handing the election to Bush in the controversial Bush v. Gore ruling.[323]

In the 2004 presidential election, Carter endorsed John Kerry and spoke at the 2004 Democratic National Convention.[324] Carter also voiced concerns of another voting mishap in the state of Florida.[325]

Amid the Democratic presidential primary in 2008, Carter was speculated to endorse Senator Barack Obama over his main primary rival Hillary Clinton amid his speaking favorably of the candidate, as well as remarks from the Carter family that showed their support for Obama.[326][327] Carter also commented on Clinton ending her bid when superdelegates voted after the June 3 primary.[328] Leading up to the general election, Carter criticized the Republican nominee John McCain.[329][330] who responded to Carter's comments.[331] Carter warned Obama against selecting Clinton as his running mate.[332]

Carter endorsed Republican Mitt Romney for the Republican nomination during the primary season of the 2012 presidential election,[333] though he clarified that his backing of Romney was due to him considering the former Massachusetts governor the candidate that could best assure a victory for President Obama.[334] Carter delivered a videotape address at the 2012 Democratic National Convention.[335]

Carter was critical of Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump shortly after the latter entered the primary, predicting that he would lose.[336][337] As the primary continued, Carter stated he would prefer Trump over his main rival Ted Cruz,[338] though he rebuked the Trump campaign in remarks during the primary,[339] and in his address to the 2016 Democratic National Convention. Carter believes that Trump would not have been elected without Russia's interference in the 2016 election,[340] and he believes "that Trump didn't actually win the election in 2016. He lost the election, and he was put into office because the Russians interfered on his behalf." When questioned, he agreed that Trump is an "illegitimate president".[341][342]

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter delivered a recorded audio message endorsing Joe Biden for the virtual 2020 Democratic National Convention. On January 6, 2021, following the 2021 storming of the United States Capitol, along with the other three still living former presidents, Barack Obama, George W. Bush, Bill Clinton,[343] Jimmy Carter denounced the storming of the Capitol, releasing a statement saying that he and his wife were "troubled" by the events, also stating that what had occurred was "a national tragedy and is not who we are as a nation", and adding that "having observed elections in troubled democracies worldwide, I know that we the people can unite to walk back from this precipice to peacefully uphold the laws of our nation".[344] Carter delivered a recorded audio message for the inauguration of Joe Biden on January 20, 2021, as the Carters were unable to attend the ceremony in person.

Hurricane relief

Carter criticized the Bush administration's handling of Hurricane Katrina,[345] and built homes in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy,[346]

Carter partnered with former presidents to work with One America Appeal to help the victims of Hurricane Harvey and Hurricane Irma in the Gulf Coast and Texas communities,[347] in addition to writing op-eds about the goodness seen in Americans who assist each other during natural disasters.[348]

Other activities