2022. 7. 19. 01:53ㆍ■ 종교 철학/천주교

The state of the Catholic Church in Canada, amid scandals and declining attendance

When he was young, Emmanuel Houle said being a Catholic was more of a routine than a religion.

It wasn’t until he attended a youth group event in his teens that he realized other young people shared his faith. This excited him and made him feel more connected to his religion. At the end of the event, he had to give a testimony of what his Catholic faith meant to him.

“From then on, it wasn’t my parents’ faith anymore,” he said. “It had become my own and one I was interested in pursuing.”

Houle, who was raised in a town outside of Ottawa, left home at 17 to join a seminary and become a Catholic priest. During the years he spent studying in Rome, he became fonder of his faith and the role it played in his life.

“I was blessed to have a taste of that life,” he said.

After six years, Houle left the seminary. He has since married and had five children. His life is busier than it once was, but he still finds time to pray, attend church and open himself to God.

Like many faithful Catholics, Houle is aware of the church’s history within Canada. He has borne witness to declining attendance and the fallout from scandals, but he has hope for Pope Francis’ upcoming week-long pilgrimage across Canada.

The Pope will arrive on July 24 in Edmonton at a pivotal time.

The Catholic Church in Canada is emerging from a pandemic with attendance rates that have been on the decline for decades. An increasing number of churches have been sold to compensate for empty pews.

The role of the Catholic Church in society is not what it once was. What used to be a pillar in the social and political life of communities has now, for some, become the building they pass on the way to the grocery store. Its reputation has been tarnished by sex abuse scandals in Canada and around the world, and after last summer, when hundreds of suspected unmarked graves were discovered on the sites of past residential schools, many were reminded of the church’s role in this country’s controversial history.

Canadian Catholics are hoping that a visit from the Pope, which includes stops in Quebec City and Iqaluit, and meetings with First Nations, can begin to address past wrongs.

The decline of the Catholic Church’s presence in Canadian society is nuanced and affected by several factors including age, immigration and which province one comes from, explained Sarah Wilkins-LaFlamme, a professor of sociology at the University of Waterloo who studies religious trends and behaviours.

From the 18th to the early 20th century the Catholic Church was a key provider of social services in Canada, including welfare, education and health care. It was an institution that many Canadians, in rural areas and cities, relied upon.

By the 1960s, when Canada’s welfare system was introduced and the government took control of social services, the church’s role in Canadian society diminished dramatically, and with it a large portion of those attending Sunday service.

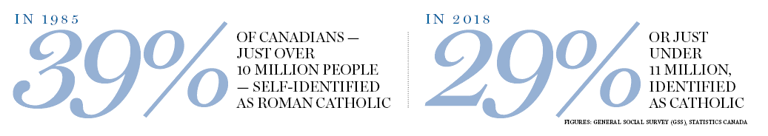

According to Statistics Canada’s 1985 General Social Survey (GSS), an estimated 39 per cent of the general population, or just over 10 million people, self-identified as Roman Catholic. In the 2018 GSS, this number was down ten points, with 29 per cent identifying as Catholic, or just under 11 million.

Over the 33 years between these surveys, the number of Catholics in Canada rose by almost 700,000 people. This number did not keep pace with the growth of the Canadian population which increased by around 11 million from 1985 (25.84 million) to 2018 (37.07 million).

The Catholic Church in Canada has also seen losses in those attending religious services and gatherings. In the 1985 GSS, 37 per cent of Catholics said they attended religious services at least once a week, 19 per cent said at least once a month, and 21 per cent at least once a year. At the time, on average, 77 per cent of Canadian Catholics attended religious services or gatherings at least once a year.

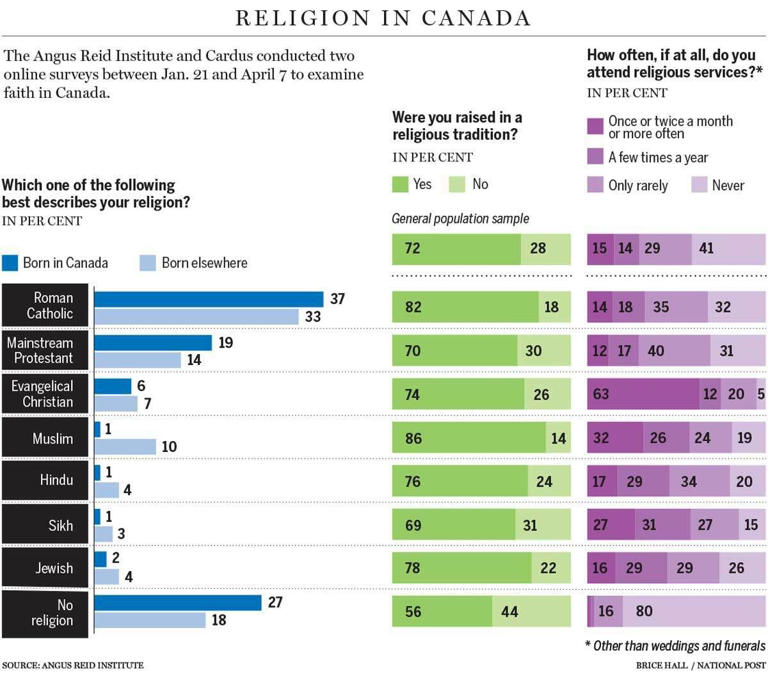

These numbers have plummeted. According to a 2022 Angus Reid Institute survey that studied the religious spectrum across Canada, 67 per cent of respondents that identify as Catholic said they attend religious services rarely or never. Only 14 per cent said they attend once or twice a month and 18 per cent said a few times a year.

It is unknown exactly how the pandemic has affected these numbers, said Wilkins-LaFlamme. But there were a lot of churches that had to close their doors to protect their members, many of whom are older

“Now the big question is, well, who’s coming back?” she said.

According to an unreleased Cardus and Angus Reid Institute survey looking at Canada’s shifting religious landscape, in 2018, around 23 per cent of Catholics attended mass, said Ray Pennings, executive vice president of Cardus. In 2019, these numbers dropped to about 19 per cent and in 2020, after the pandemic hit, attendance at Catholic masses fell to 12 per cent.

James Milway, chancellor of temporal affairs at the Archdiocese of Toronto, said during the pandemic the archdiocese had a decline in revenue that comes from parishioners, but it was not as severe as the decline in attendance, which was about 50 per cent.

When COVID first hit, the archdiocese was preparing layoff plans, said Milway, but when it received a Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy, it was able to keep its whole staff on payroll. Operating costs also declined, which made up for the loss in revenue, said Milway, but there were still parishioners that dropped cheques off at rectories or made regular payments through their banks during the pandemic.

“So, financially, we were fine,” said Milway. “But the bigger problem we’ve got is getting people back to mass.”

Many Catholics have known their religion since birth. They were born and baptized Catholic, raised by Catholic parents, and attended Catholic school.

Matt Vaughan said his Catholic faith became important to him in high school at the age of 15. After experiencing God at a church conference, he said church went from being a place he went to on Sunday mornings to something of “beauty and importance.”

Vaughan is now 33 and lives in the Clayton Park community of Halifax. He works as the communications coordinator for Saint Benedict Parish in Halifax where he also attends as a parishioner. Before joining this church, Vaughan also worked as a youth minister at a Catholic church in Saskatoon.

As a kid growing up in Cole Harbour, N.S., Vaughan said he remembers when masses were full and he had to arrive early to get a good spot in the pews. Now, Vaughan’s childhood church is part of a three-parish system; it was combined with two other churches because of a decline in parishioners and priests.

Saint Benedict Parish is also a result of the combination of three churches that were shut down and then put back together into a new church, said Vaughan. While Saint Benedict Parish is one of the bigger churches in Atlantic Canada, he said he has seen a decline in church attendance firsthand throughout his life.

In the Ottawa valley, where Houle attends church, he said attendance now is mostly the same as pre-pandemic. There is some hesitation from those who are worried about getting sick, but for the most part, he said, they are back to normal.

The reality is different for the parish Houle grew up in, which is just outside of Ottawa. Since reopening, his childhood church has seen lower attendance rates. He said he cannot say for sure if the decline is because of the pandemic or if the people in the small community are just not interested in attending church.

Because of a decline in participation in religious activities, Catholic dioceses across the country have had to close churches and sell off their properties to compensate for the loss of income that would usually come from full masses.

This is seen most vividly in Quebec, where Catholic church closures have become increasingly common. In 2018, 30 of 54 churches in the Diocese of St-Jérôme were slated for closure, according to a report by the diocese. Even the oldest churches in the province may not be safe, as the fate of the historic 19th century Saint-Jean-Baptiste church in Quebec City, which has been closed since 2015 and needs structural work, is still undecided.

In Montreal, where Mark Twain once noted that “you couldn’t throw a brick without breaking a church window,” many shuttered Catholic spaces are being sold to developers and turned into hotels, community centres, restaurants, libraries and condos.

Most recently, the Catholic Archdiocese of St. John’s, Nfld., has had to list 18 of its properties for sale as part of bankruptcy filings. In 2021, the archdiocese was found liable for operating Mount Cashel Orphanage where more than 100 boys were sexually abused. They have been ordered to compensate the victims more than $50 million.

In Quebec, more than 2,500 victims of sexual abuse by Catholic clergy are asking the Pope to deliver “swift justice” ahead of his visit to Canada. Lawyers for the victims, who have yet to go before the court, said they issued a letter directly to Pope Francis on July 14.

For faithful Catholics like Vaughan and Houle, reckoning their religious identity with institutional wrongdoings, including sexual abuse scandals and the church’s history with residential schools, is not easy.

“I simply can’t say the Church is perfect,” said Vaughan. “God and Jesus are perfect, but the Church is not perfect at all.”

In Canada, religious affiliation and participation in religious activities have been on the decline across all religious groups for decades. According to the 1985 GSS, 90 per cent of Canadians aged 15 and older had a religious affiliation. This number dropped to 68 per cent in the 2019 GSS.

The proportion of people who participate in religious activities at least once a month – meaning attending services or observing personal forms of worship – nearly halved, from 43 per cent in 1985 to 23 per cent in 2019. Those that participate at least once a week declined 16 points, from 46 per cent in the 2006 GSS to 30 per cent in 2019.

There is no simple answer to why there has been a decline in religious affiliation and attendance across the country, said Wilkins-LaFlamme.

When considering Catholics specifically there has been some intergenerational loss that began in the 60s. Wilkins-LaFlamme said that children and grandchildren of traditionally Catholic families have tended to not adopt the same religious identity as their parents and grandparents.

While the church may be losing numbers due to age, the Catholic Church in Canada gains many members from immigration, especially from Central and South America, parts of Africa, Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia, said Wilkins-LaFlamme.

According to the Angus Reid survey, 33 per cent of respondents born outside of Canada said they were Roman Catholic. This is compared to 18 per cent who said they have no religion, 14 per cent who said they were Mainline Protestant — which includes Anglican, Protestant, Lutheran and United Church — and 10 per cent who said they were Muslim.

“Immigrants are feeding the Catholic Church because they are usually more actively religious than the white European Catholic populations of Canada, both in French-speaking and English-speaking Canada,” said Wilkins-LaFlamme.

There is also the case of Quebec, where religious affiliation is high, but participation in religious activities has “hit rock bottom,” said Wilkins-LaFlamme. According to the 1985 GSS, 51 per cent of Catholics in the province said they participated in religious activities at least once a month. In 2019, participation hit 14 per cent. Within this period, the share of Catholics in Quebec fell from 87 per cent to just 62 per cent.

“We call this cultural Catholicism,” said Wilkins-LaFlamme. “They don’t necessarily attend regular religious services, but they are still affiliated with a Catholic identity.”

Since before his papal inauguration, Pope Francis has been known to represent a more open-minded Catholic Church and has made efforts to address past wrongs.

He has spoken about accepting those in the LGBTQ+ community and taking action on climate change. He has also made efforts to address criticisms that the church limits the roles of women. On July 13, Pope Francis named three women to the Dicastery of Bishops, the Vatican office which oversees the selection of new bishops.

In April, with Indigenous delegates from Canada in attendance, Pope Francis apologized from the Vatican for the role the Catholic Church played in the residential school system.

“For the deplorable conduct of those members of the Catholic Church, I ask for God’s forgiveness and I want to say to you with all my heart: I am very sorry,” he said.

While this was a start, the apology only mentioned “a number of Catholics” who had been involved. The National Council for Truth and Reconciliation’s Survivors Circle has drafted an apology that asks the Pope to apologize and take accountability for implementing Canada’s Indian Residential School assimilation policy on behalf of the Catholic Church.

The Survivors Circle released the draft publicly in June and submitted it to the Canadian Council of Canadian Bishops (CCCB).

In a statement, the CCCB said they “are fully committed to building relationships and walking together with Indigenous people from across Canada.” Along with meeting with Indigenous community leaders over the past months and pledging to raise $30 million for reconciliation efforts, there were members of the Council at a recent Survivors Circle meeting in Winnipeg where they discussed the Papal apology.

While members of the Survivors Circle hope the Pope’s apology is close to the draft they provided, Veldon Coburn, professor at the Institute of Indigenous Research and Studies at the University of Ottawa, said the Church will most likely craft a speech that is not identical but addresses the points that survivors want to hear.

“This could make church history,” Coburn said. “And relations may begin to improve.”

Coburn also noted that there is a portion of Indigenous peoples in Canada that identify as Catholic. According to Statistics Canada’s 2011 National Household Survey, 37 per cent of those that self-identify as Indigenous in Canada also identify as Catholic, said Wilkins-LaFlamme.

Faithful Catholics, like Vaughan and Houle, are hoping that the Pope’s visit will bring about reconciliation. Though they understand, that healing takes time.

Houle said he hopes the Pope’s visit to Canada will be an opportunity for the Catholic Church to request forgiveness from Indigenous communities.

“Forgiveness is a two-way street,” he said. “The Church may offer it, but it has to be accepted.”

'■ 종교 철학 > 천주교' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 유흥식 추기경, 교황청 성직자성 장관 (0) | 2022.08.28 |

|---|---|

| 유흥식 추기경, 로마 교황청 성직자부 장관 (0) | 2022.08.28 |

| ■ 20220417 SUN 부활절(Easter/復活節) (0) | 2022.04.18 |

| ■ 원주 용소막성당(原州 龍召幕聖堂) (0) | 2022.03.25 |

| "드디어 5년 뒤 완공된다"..가우디 150년 역작 '사그라다 파밀리아 성당' (0) | 2021.05.01 |